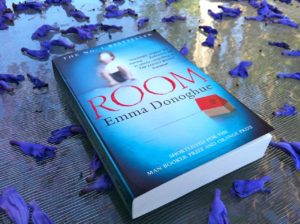

Room by Emma Donoghue and the trauma culture

Trauma, as Ann Cvetkovich states in her essay An Archive of feelings is the ‘subject of a discourse that has a history’. In fact, in the nineteenth century trauma referred to a physical wound and become later on in the century associated to mental and physic distress. Thanks to the development of different ways of divulgating knowledge and the much larger freedom of speech, the matter of trauma became increasingly discussed in the public sphere within various fields and domains. Therefore, this essay analyses how the various aspects of trauma are represented in Emma Donoghue’s bestseller Room, which is a novel that fits perfectly in what Ann Cvetkovich calls ‘trauma culture’. The essay starts with a specific focus on sexual abuse as an extremely complex concept, analysing the development of sex and rape conception throughout the last two centuries, citing also Foucault’s study of sexuality The will to knowledge: The history of sexuality. The second part of this essay is dedicated to the effects of the isolation and captivity that the characters of Room Ma and Jack experience, highlighting Emma Donoghue’s approach to the issue with a particular attention on the way she describes the details through the voice of the five-years-old Jack. The last part of my writing portrays the popular response to trauma and above all the role of literature and mass media face to violent and traumatic experiences, which become a marketing subject, as Steve Almond underlines in his article Liar, liar, best-seller on fire. Special references to some critical writings such as Violence and the Cultural Politics of Trauma by Jane Kilby and Anne Rothe’s Popular Trauma Culture. Selling the Pain of others in the Mass Media are also noted in this section.

Trauma, as Ann Cvetkovich states in her essay An Archive of feelings is the ‘subject of a discourse that has a history’. In fact, in the nineteenth century trauma referred to a physical wound and become later on in the century associated to mental and physic distress. Thanks to the development of different ways of divulgating knowledge and the much larger freedom of speech, the matter of trauma became increasingly discussed in the public sphere within various fields and domains. Therefore, this essay analyses how the various aspects of trauma are represented in Emma Donoghue’s bestseller Room, which is a novel that fits perfectly in what Ann Cvetkovich calls ‘trauma culture’. The essay starts with a specific focus on sexual abuse as an extremely complex concept, analysing the development of sex and rape conception throughout the last two centuries, citing also Foucault’s study of sexuality The will to knowledge: The history of sexuality. The second part of this essay is dedicated to the effects of the isolation and captivity that the characters of Room Ma and Jack experience, highlighting Emma Donoghue’s approach to the issue with a particular attention on the way she describes the details through the voice of the five-years-old Jack. The last part of my writing portrays the popular response to trauma and above all the role of literature and mass media face to violent and traumatic experiences, which become a marketing subject, as Steve Almond underlines in his article Liar, liar, best-seller on fire. Special references to some critical writings such as Violence and the Cultural Politics of Trauma by Jane Kilby and Anne Rothe’s Popular Trauma Culture. Selling the Pain of others in the Mass Media are also noted in this section.

Sexual abuse as a social problem and its representation in Room

Analysing the numerous traumatic aspects that characterize Emma Donoghue’s novel Room, it is worth starting with an important social problem such as the rape and sexual abuse. This issue has always risen ongoing debates, as it is unfortunately an omnipresent threat all over the world. It is not a case that Emma Donoghue inspired her novel to the dramatic Fritzl case emerged in April 2008 when an Austrian woman finally found the strength to tell the police that she had been held captive for twenty-four years in the basement area of the large family house by her father, who raped her several times during the imprisonment. The sexual abuses led Elizabeth Fritzl into nine pregnancies, seven of whom resulted as successful births.

We do not have to think very far to remember the sad event of New Year’s Eve 2015, where more than a hundred women where sexually assaulted by a group of young men in the German city of Cologne. This event has led to a big argument, above all when the Cologne imam Mr Abu-Yusuf stated that:

The events of New Year’s Eve were the girls own fault, because they were half naked and wearing perfume. It is not surprising the men wanted to attack them. [Dressing like that]is like adding fuel to the fire.

Therefore, the concept of rape seems to have always been very complex and until not too long ago, it was an undiscovered field all over the world, with lots of questions left in the hands of scientific and medical experts. Rape and sex in general, is a very complex subject and is conceived differently within different eras, cultures and religions. Nicola Gavey in Just Sex? The Sexual scaffolding of rape tries to analyse one of the common popular reactions to the allegation of rape, which characterised the mid twentieth century, which questions whether women are really the passive victims into the mechanism of sexual assault or whether it is a matter of female sexual provocation against men’s natural predisposition to sexual acts:

For instance, while women were portrayed as sexually passive in relation to men, they were also imbued with a dangerous lurking sexuality that could be invoked in all sorts of ways to explain and justify rape. This underlying magnetically beckoning sexuality ties in with the notion of female sexual provocation that has been crucially invoked to diminish male agency in rape and to minimize the harm that rape might do to women. This is the idea that women are really responsible for rape by crossing some invisible boundary of sexual chastity to turn on men’s (naturally rampant) sexuality.

In other words, the main debate, both within and outside feminism was considering whether ‘rape is about sex or it is about violence and power’.

This question raised a deep interest in the male psychological side of rape, which paradoxically sees the man perceiving the protests of the raped women as an act of complicity, provoked by an unconscious rape wish, rather than an attempt to defend herself and escape. In regard to this argument Nicola Gavey considers a meaningful passage from Susan Griffin’s Rape: The All American crime:

Still, the male psyche persists in believing that, protestations and struggles to the contrary, deep inside her mysterious feminine soul the female victim wished for her own fate.

Indeed this matter is discreetly underlined by Emma Donoghue in Room, when the kidnapper Old Nik, before sexually abusing of Ma, addresses to her ‘doing a kind of laugh’ with the following sentence: ‘I know what you need, missy’.

Moreover, this victim-blaming’s conception, which has characterized the community attitude towards rape until the 70’s, created in abused women a sense of self-blaming for violence against them.

Therefore it is very important that starting from the late 60‘s, the sexual abuse and rape matter have increasingly been reported and known in the popular culture, contrary to what was happening in a period when women who had experienced rape could not find their freedom to share their experiences. This divulgation of knowledge was helped by a multiplied disclosure on sex in all its different sides, going beyond the taboos that limited the freedom of speech in the field. As also Foucault highlights in The will to knowledge: The history of sexuality:

The essential point is that sex was not only a matter of sensation and pleasure, of law and taboo, but also a truth and falsehood, that the truth of sex became something fundamental, useful, or dangerous, precious and formidable’.

With this statement Foucault stresses on the fact that the increasing interest in the field of sexuality led to a more accurate analysis differentiating the numerous fundamental and useful aspects that characterize this complex topic.

In the first part of 70’s in United States, a group of feminists started mobilising, founding an anti-rape movement which established some activities to support sexual abuse survivors and to combat violence against women. In Washington DC in 1972, the first Rape Crisis Centre was formed and began offering a telephone crisis line for victims of sexual violence. This event signed the start of a growing women’s movement all around the world, creating consciousness about rape, with the key objective of replacing the traditional victim-blaming views about women into a ‘pro-woman stance’. Particularly interesting is the passage of Susan Brownmiller in her bestselling book Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, where she affirms that rape is a ‘conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear’. Consequently, this explains how the sexual assault was perceived by men as a ‘purposeful act of control. In some cases rape was an act of manhood, a rite of passage, or a form of male bonding’. Therefore according to what Brownmiller states, the sexual abuse by men can be considered in a certain way a practice of affirming their masculinity and power through violence and fear towards women.

Room, published in 2008, fits perfectly into a century where women are increasingly denouncing acts of violence against them, finding more space and ears ready to make their personal experiences known thanks to mass Medias and the growing popular interest in sharing traumas. According to Sarah Blackwood, ‘Room is a formally inventive story about domesticity and sexuality’. She adds that ‘[it] asks us to perform the politically important task of closely examining women’s experience of all those topics’. A later interesting example of denouncing crimes could be the Lady Gaga’s song Till it happens to you. According to the singer this is as an anthem for a movement that condemns sexual assaults and gives hope to the survivors. In fact, her astonishing performance on 2016 Oscar award ceremony stage sees Lady Gaga joined by a group of sexual assault victims with Not Your Fault written on their arms.

Emma Donoghue in Room deals with the topic of rape with an impressive sensitivity, helped by the fact that the entire novel is told by the 5 year old captive Jack, who describes every moment with that particular naive way, typical of a child. He sleeps in the wardrobe and each night he hears the ‘creaks’ of the bed while Old Nick abuses his mother without knowing what is really happening, ‘tonight it’s 217 creaks. I always have to count till he makes that ‘gasp’ sound and stops. I don’t know what would happen if I didn’t count, because I always do’. This naive unconsciousness is consistent throughout the story and Emma Donoghue takes advantage of Jack’s voice to describe the details of the trauma’s effects on his mother. She manages to make the reader understand the depression Ma is going through with the following passage:

Today is one of the days when Ma is Gone. She won’t wake up properly. She is here but not really. She stays in bed with her pillows on her head. […]Ma’s like a zombie today.

According to some researchers conducted and reported by the National Violence Against Women Prevention Research Centre of the Medical University of South Carolina, the depression is a common mood disorder within rape victims that occurs when feelings associated with sadness and hopelessness continue for long periods of time:

30% of rape victims had experienced at least one major depressive episode in their lifetimes, and 21% of all rape victims were experiencing a major depressive episode at the time of assessment.

Therefore, this trauma recurs in Emma Donoghue’s novel and is frequently reported through Jack’s eyes, even once they have escaped Room:

When I wake up in the morning Ma is Gone. I didn’t know she would have had days like this in the world. I shake her arm but she only does a little groan and puts her head under the pillow.

Furthermore, the topic of the suicide is particularly intense and cleverly represented by the writer. Suicide is a very common reaction to rape; in fact, Kilpatrick’s research on The Mental Health Impact of Rape shows that:

One-third (33%) of the rape victims ever thought seriously about committing suicide. Rape victims were 4.1 times more likely than non-rape victims to contemplate suicide and were 13 times more likely to have attempted suicide.

Jack attends the terrible scene of her mother’s suicide attempt; in fact he is the one saving her. After the talk show interview, she is exhausted from confronting her trauma, moreover it seems like she is pervaded by a sense of guilt when challenged by the interviewer claiming that she could have let Jack being adopted. The way Emma Donoghue describes the scene of the suicide, seen from the perspective of the 5 year-old boy and using words of a helpless and innocent child, creates a tragicomic feeling that enhances the powerful drama of the novel:

She doesn’t switch on, she doesn’t groan or even roll over, she’s not moving when I pull her. This is the most Gone she’s ever been. […] She’s a zombie, I think.

After having analysed the traumas that characterise this first sensitive aspect of Room it seems in a way, a small manifesto denouncing or better, remembering that sexual abuse and rape is still a dangerous and present social problem so it is worth focusing on a second interesting matter that is well interpreted by the writer: the captivity and its effects.

The effects of isolation and captivity in Room

The imprisonment and the trauma related to it are the most complex and particular aspects of Room as both Ma and Jack are experiencing the same situation but in two completely different ways and with different outcomes. The experience that the two characters are going through is without the shadow of a doubt, tragic and traumatic at the same time. Emma Donoghue highlights the strong bond mother-son that this situation builds and strengthening especially this specific subject. In fact, during an interview at The Late Late Show on RTÉ ONE she affirms that ‘the parent-child bond is an intimate magical relationship’ and she wanted to ‘shine a light on the everyday heroic love between parent and child’ in such an enclosed and claustrophobic environment. Considering Jack’s experience of their captivity, he never realises about their situation as Ma never clarify for him they are prisoners because she does not want him to grow up thinking he is held captive and she helps him seeing the world in a meaningful and magical way inside Room. Therefore Jack spends his first five years believing that anything that is not inside room exists. He makes friends with all the objects inside the cellar and all of them become real characters with a gender, for example Door is male and Plant is female. As Emma Donoghue explains in an interview at Richard & Judith Spring 2011 Bookclub she was inspired by her children’s behaviour as ‘they turn everything into a toy’ and she adds that if they did not have friends and games they ‘would make friends with a knife and a fork’. This sort of game that Ma invents to try make at least her child’s life happier appeared already on the screens in 1997 with the Italian tragicomic movie Life is beautiful directed by the Italian comedian Roberto Benigni. Similarly, a father, deported and enclosed with his six years-old child in a concentration camp during the Holocaust in Italy hides their true situation from his son explaining him that the camp is a complicated game in which he must perform the tasks that Guido gives him in order to win a prize. Going back to Room, at a certain point the illusory locus amoenus where Jack has been living for five years becomes suddenly a frightening nightmare as soon as Ma decides to tell him the ‘true story’ as he calls it, unveiling the secret of the outside world and her kidnapping. Jack finds himself face to face with a reality that he has never known and does not understand, he is disorientated and when Ma tries to explain him that she was living in a house with her parents, his firsts thought is ‘A house in TV? […] That is ridiculous, Ma was never in Outside’ (p.104). Jack struggles to find a sense in Ma’s confession but it seems to be more confused ‘I’m trying to understand. Swiper no swiping. But I never heard of swiping people’ (p.116).

The effects of this isolation that the 5 year old boy experienced are sensibly reported by the writer. Especially the extreme breastfeeding raised a big debate as considered by many very disturbing: ‘I lift her T-shirt again and this time she puffs her breath and let me, she curls me against her chest’ (p.199). This scene is very emblematic as, on the one hand it embodies a complex post-traumatic stress disorder where Jack shows issues with relationship boundaries, finding himself asking her mother to breastfeed him at the age of five. On the other hand this extremely intimate act of love can be perceived as a way for Ma to protect him and spoil him in order to make him feel comfortable in an environment that she has built up by herself. This scene appears a couple of times throughout the novel. One of them is from Jack’s Grandmother who stares at them and addresses Ma with an astonished sentence ‘You don’t mean to say you’re still…’(p.268). The last time Jack was trying to get some milk from Ma’s breasts she forbids him to pull her T-Shirt up and explains:

‘I don’t think there’s any in there […] Well, the thing about breasts is that if they don’t get drunk from, they figure, OK, nobody needs our milk anymore, we’ll stop making it’ (p.378).

This speech marks the start of a new journey that sees a different and grown-up Jack, ready for a future with plenty of new discoveries. In regards to Ma’s personality, she is an extraordinary character. As Emma Donoghue declares at Richard & Judith Spring 2011 Bookclub interview ‘Ma is the best most vital, energetic, intelligent and creative mother I could have imagined’. She has been inspired by the myth of Danaë, mother of the Greek hero Perseus. Despite her amazing strength as a mother, the writer gives room to some weaknesses gathered during her imprisonment. One of the first feelings that Ma unveils above all is fear, mainly when facing Old Nick. The reader can really perceive terror within the characted when talking to the kidnapper in an extremely apologetic way. For example when he enters the door and Room smells of food she promptly answers ‘Mmm, sorry about that [..] we had curry’ (p.85). In the same passage she asks Old Nick to put an extractor fan on and when he states that they will be discovered if he does, she apologises again ‘Oh, sorry […]I didn’t think […] I am really sorry I didn’t realize about the smell and that a fan would – […] I shouldn’t have asked for a fan, it was dumb of me, everything’s fine’ (pp.85-86). This sort of panic that Ma experiences on the one hand is due to Old Nik’s violent behaviour towards her, on the other hand it hides a little hope in the deep inside of her that one day she will manage to get out of that cellar. In more than one circumstance she personally tells Jack that Old Nick scared her and describes to him a few cases where she was attacked and beaten:

The first time he opened the door I screamed for help and he knocked me down, I never tried that again […] I used to be scared to go to sleep, in case he came back (pp. 117-118).

She even tells him about the time she tried to escape but Old Nick assailed her again ‘He jumped up and twisted my wrist and got the knife’(p.121). She knows perfectly that if she ever tried a stunt to escape he could go away anytime and let them starve. The effects of her trauma caused by the captivity though are still perceivable even after she is freed from the cellar. Lynn Cinnamon’s article on Room is particularly interesting as she states that:

Jack’s thoughts are a unique lens to show Ma’s struggles. His mother’s psychological and existential crises bubble to the surface once they are free, and Jack’s immediate safety isn’t her entire world anymore.

In relation to this specific aspect, Emma Donoghue deals with a series of post traumatic disorders such as cognitive distortions and a imprecise perception of herself, while Ma is trying to find a new balance in her new routine. This is underlined by an appointed sentence she addressed to Jack ‘I know you need me to be your Ma but I’m having to remember how to be me as well at the same time’. This highlights the fact that there is a part of Ma that has been left behind and that she cannot find anymore. We also learn that she experienced an additional trauma linked to the loss of a first baby in Room, before giving birth to Jack, which stresses on reminding us the endless strength of Ma proven throughout the novel.

Having analysed the several traumas that come into view in Room and the way they are described by the writer and the 5 years-old narrator Jack, it is worth focusing the attention now on the impact that the traumas had on the people in Emma Donoghue’s fiction. Also, I will analyse the popular culture’s response face to traumas and citing Anne Rothe’s words ‘what has been variously dubbed […]misery literature’.

Trauma within the popular culture

Starting from the crucial point of the liberation of Jack and Ma, they find themselves suddenly in the spotlight, dealing with journalists and paparazzi hounding them for statements, pictures and interviews. Jack gets to know their position towards the media as he sees themselves in the TV news and shouts ‘Ma it’s us. It’s us on the TV!’(p.205). And also, he starts feeling the media’s pressure on his history as soon as his eyes fall onto a newspaper describing the ‘Bonsai Boy’ or ‘Miracle Jack’ as ‘the product of his beautiful young mother’s serial abuse at the hands of the Garden-shed Ogre’(p.269). The article continues stressing on the traumatic experience saying that ‘experts cannot yet say what kind or degree of long-term developmental retardation he might be effected by’(p.269).

According to a blog post by a dental clinic Lewis Center employee, the psychiatrist on duty who follows the rehabilitation of Jack and his mother Dr. Clay explains to Ma that ‘Celebrity is a secondary trauma’(p.383) and suggests for her to create new identities by changing at least their surname. This is in order to attract less attention, above all in regard to Jack in view of his school career. Ma’s categorically rejects Dr. Clay’s idea, even though she experiences a tragic and hurting moment while being interviewed on a TV talk show. Jack who is actually watching his mother from a corner of the same room, describes her reactions as an expression of anxiety, disappointment, frustration and sadness as the interviewer gets more and more into the many details of her past. For example, Jack sees that ‘Ma’s hands are shaking, she puts them under her legs’(p.290). The journalist, or the ‘woman with puffy hair’(p.289) as Jack describes her, challenges Ma with insolent and very personal questions that she knows are drawing the attention of the spectators such as ‘Was that before or after the tragedy of your still-birth?’(p.290). She even dares talking about biological relationship between Jack and the captive Old Nick alluding to his paternity asking her:

Did you get the sense, over the years, that this man cared –at some basic human level, even in a warped way- for his son? […] I was wondering whether, in your view, the genetic, the biological relationship- […] and you never found that looking at Jack painfully reminded you of his origins?’(pp.293-294).

At this point, Ma is irritated and answers talking in between her teeth ‘Jack’s nobody’s son but mine. There was no relationship’(p.293). The fact that Emma Donoghue adds the part of sharing the trauma within the public sphere into her novel is a really clever choice to represent the popular response to traumas. As Ann Cvetkovich underlines in her An archive of feelings according to some people ‘we are living in a trauma culture’. In fact, she highlights how people are becoming more and more interested in violence cases as they get emotionally involved. She reports Mark Seltzer’s quote about what he calls ‘a wound culture’ and describes ‘the cultural obsession with serial killings and other sites of violence that produce a pathological public sphere’. Therefore it is necessary to understand if and how the divulgation of trauma experiences is beneficial to the contemporary popular culture. According to Ann Cvetkovich, trauma constitutes an ‘archive of feelings [made by] many forms of love, rage, intimacy, grief, shame, and more’. As trauma has always been in most cases unspeakable and unpresentable, Cvetkovich points up the importance and the necessity of trauma in being shared and divulged through something more powerful than the ‘conventional forms of documentation, representation and commemoration’; consequently she states that the trauma she experiences gives rise to ‘new genres of expression, such as testimony and new forms of monuments, rituals, and performances that can call into being collective witnesses and public’. In regard to this point Anne Rothe in her Popular trauma culture deals with the rise of popular psychology helped by the strong American individualism that suppresses the role of social institutions and defines people as free agents of their actions and destiny. This ideology has dominated since the 1980s, prepared the ground for the introduction of self-help books and daytime TV talk shows. Above all with regard to the latter, Ann Rothe defines the Oprah Winfrey Show as the starting point for a new and widely known TV genre that disseminated popular psychology through the production of talk, especially on violent and sexual victimisation experiences whose purpose was mainly to simulate a group therapy followed by millions of spectators.

Despite the proliferation of personal experiences broadcasted by TV talk shows, in Ann Rothe’s essay also emerges the triumph of a new literary genre that revolves around the memoir as a ‘result of its reorganisation around trauma’, known as misery memoirs or misery literature. This texts ‘represent horrific real-life experiences, particularly child abuse, illness and addiction, according to the plot paradigm dominant in popular trauma culture’. This new genre seems to actively adapt to the population’s demand, becoming quickly involved in the market and advertised on TV talk shows. Consequently Steve Almond explains on one of his article on New York Times that in order to sell a book nowadays:

It’s no longer enough to simply offer besieged publishers a nuanced work of imagination. [Publishers] need an aspirational figure the marketing people can dangle as interview bait. They need a pitch dramatic enough to resonate with the frantic metabolism of our perpetual news cycle. Because [those] books are about 100 times more likely to get reviewed and featured on National Public Radio and anointed by Oprah.

This underlines the fact that the relation between the innovative way of sharing traumas, thanks to TV talk shows as well as misery literature and marketing aspect lead to the failure of what is called trauma culture. As Jane Kilby highlights in Violence and the Cultural Politics of Trauma:

The success of daytime talk and the daily parade of women offering testimony to painful realities serve for many critics as perhaps the best example for demonstrating the limits if not outright failure of a cultural politics trauma.

In regard to this specific matter, Jane Kilby cites the German sociologist Frigga Haug’s anecdote in order to ‘attempt to demonstrate a relationship between sex scandals and the demands and opportunities of the global free markets’. While waiting for her luggage at the airport Haugh finds herself watching a TV talk show where a woman was crying where the conductor was encouraging her to tell her story in deeper way, with more details. Soon after that ‘the showmistress interrupted the whole scene, took a book from a nearby table and encouraged all of us to come out and reveal our secret that we had all been abused as children’. This scene clearly sums up Kidby’s theory of a downfall of the cultural politics of trauma that goes against Cvetkovich’s belief in trauma culture as a ‘work of therapy’.

Emma Donoghue’s international bestseller Room, written on the basis of the true story of the Fritzl case was shortlisted for the Man Booker and Orange Prizes and has sold over two million copies. Furthermore the book inspired the homonymous film directed by Lenny Abrahamson and candidate to the Oscar 2016. On the one hand it is clear that Room has found its way throughout many talk shows and TV programs such as the already mentioned Richard & Judith Spring 2011 Bookclub, The Late Late Show, The Hollywood Reporter. Nevertheless, as the writer herself admits, the novel was not meant to be a crime novel but it is supposed to focus more on Jack, the superhero character and mother and child relationship. At this point the perception of Room acquires a subtle ambivalence. It is clear that Room was written following the popular demand of the trauma culture characterised by the denunciation of sexual abuses, violence against women and children with a sophisticated allusion to feminism. Therefore ‘Room is a misogynistic exploration of the suffering misogyny causes women’ which still preserves some characteristics typical of a fairy tale.