The Best Film You Missed Last Year: Snowpiercer

Beware! Spoilers Ahead!

It is unlikely many will have managed to catch Snowpiercer due to a disagreement between director Bong Joon-ho and The Weinstein Company which resulted in a minimal release for the film. This is made all the more unfortunate due to the fact that, in my opinion, Snowpiercer is an excellent film and it would surely have been a success (at least critically) if it had been made more widely available. For now, it remains a cult masterpiece.

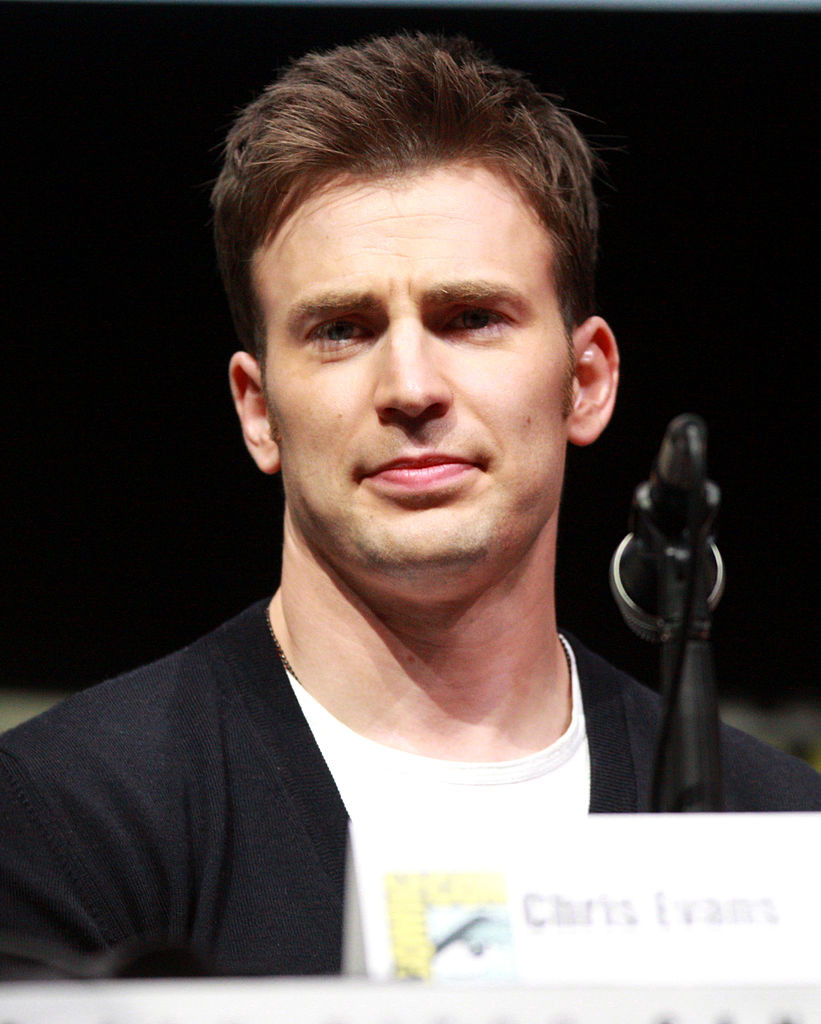

Based on the French graphic novel, Le Transperceneige by Jacques Lob & Benjamin Legrand and Jean-Marc Rochette, Snowpiercer tells the story of the remaining survivors of a ravaged world who are forced to seek shelter in a perpetually moving train. The survivors have existed in this way for 17 years and have since lost sight of the possibility of a final destination and a future outside of the train. The tail-sectioners languish in their squalid living conditions and are too fearful and disillusioned to protest. From the poor at the tail end to the elite at the nose, throughout the film the train becomes an increasingly obvious allegory for hierarchical society and tensions between class culture. Early on it is discovered that the guards responsible for keeping the tail-sectioners down had, in fact, ran out of bullets years ago. The poor have long since required proof that they are wholly and completely under somebody else’s control. Then Curtis, the film’s protagonist, (Captain America‘s Chris Evans) finally manages to inspire a rebellion.

Throughout the film, Curtis and his increasingly dwindling group of brave followers pass through train cars each as different from their own experience as entire worlds. They are, however, almost always windowless and claustrophobic. In the centre of the train, they come across a classroom of children chanting bizarre mantras, led by the brilliant Alison Pill (with a delightful cultish gleam), who dissuades her pupils from attempting life in the outside world (“What happens if the engine stops?” – “we all freeze and die!”) The classroom’s décor is almost a rainbow fairground compared to the dank Victorian slum the tail-sectioners emerged from. This scene proficiently exhibits the indoctrination of children, “train-babies”, who have never known life outside the train, through creepy sing-song adages and slick, cartoon propaganda.

The cinematography is beautiful: from the sprawling frozen wastelands of the outside world to the darkened and claustrophobic prison of the tail section and the luxurious surroundings of the privileged front end. Furthermore, particularly intriguing is the simple but effective visual shorthand the film employs to demonstrate Curtis’ internal struggle. Left represents back (to squalor and subjugation but also home) whereas right indicates forward (into the unknown, seeking answers but likely finding death). In moments of doubt or clarity, Curtis looks one way or the other before finding the strength he needs to continue on.

With a cast as stellar, as this one, it is no surprise that the acting is brilliant all round, from roles small and large. Particularly of note are Tilda Swinton and Chris Evans. Swinton plays Minister Mason, a representative of Wilford (the train’s inventor), who visits the tail end in order to viciously reinforce the ideology that keeps the huddled crowd in their place. From her grimy, jutting teeth to her broad Yorkshire accent, she is utterly mesmerising in this role. She exudes brutal authority as she administers cruel justice to those she mercilessly aids in oppressing. As those familiar with Evan’s work would expect, he turns out a truly affecting performance though the moments of unexpected anti-heroism and darkness are particularly striking and they transform his performance into a great one. Early in the film, there are hints at a violent and damaged side to Curtis – an aspect of his character I was worried would be confined to occasional offhand remarks. Thankfully, Curtis quickly confirms his reputation when sacrificing one of his closest friends, though not without consternation, in the effort to further his journey along the train. Towards the end of Snowpiercer, Curtis delivers a shocking (and beautifully performed) monologue detailing his history with crimes as unthinkable as murder and cannibalism of children. He is almost the antithesis of Steve Rogers, who is good and kind and just almost to a degree of banality. Curtis is somebody you simultaneously root for and are horrified by.

One of my favourite aspects of Snowpiercer is the fact that it allows its audience to be confused, to not have all of the answers all of the time. For example, early on Curtis confides in Gilliam (John Hurt) about his fears of not succeeding as the leader of the rebellion due to having ‘two good arms’. At this point in the film, this assertation is a baffling non sequitur. However, later it becomes clear that the loss of limbs, in the world of Snowpiercer, serves as a reminder of sacrifices given in the early days of Wilford’s train when the tail-sectioners literally cannibalised themselves for food.

I understand the complaint that the film is sometimes quite overt with its attempts at metaphor and social commentary but for me these allusions were welcome ones. Snowpiercer is consistently thought-provoking and always committed to toeing the line between arthouse and action. Personally, my only noteworthy gripe would be the casting of Wilford. Ed Harris is obviously a great actor and does fine by the role but I did feel that he was slightly treading on old ground due to his appearance as a similarly omniscient creator in The Truman Show.

Earlier this year, I watched the excellent Memories of Murder, a film that Bong Joon-ho also co-wrote. The murder investigation in the film remains unsolved by the credits. In the final moments, the protagonist (played by Song Kang-ho, who also appears in Snowpiercer), simply stares into the camera. Viewers have discerned various things from this look. Personally, I feel that the endings of Memories and Snowpiercer share a similar feeling. The atmosphere lies somewhere between hope and hopelessness: a tone that feels right for both films.

Snowpiercer is one of the most inventive films this year and also one of my favourites. If you like the idea of intelligent sci-fi with lashings of social commentary and stunning action set pieces… I wholeheartedly recommend it. It is a travesty that this film hasn’t received the sort of release and ultimately the praise that it deserves.

Written by Juliette Curran